“Designed for humans first and machines second, microformats are a set of simple, open data formats built upon existing and widely adopted standards.”Through the use of these widely adopted standards, publishers can encode additional semantics into the HTML markup of web pages. This gives the pages meaning above and beyond the face value of the HTML elements, allowing them to be consumed, remixed, and mashed up. For example, by adding some semantic markup to a web page that describes an upcoming event, properties such as the event dates can easily be extracted and used by other services and software, like calendars and personal organizers. Microformats are all about representing semantic information encoded within a web page, allowing that information to be leveraged in ways that were possibly never conceived by the original publisher. The idea to put more semantic information directly into HTML is nothing new — people in the web industry have been discussing this concept for over ten years — but, through the efforts of many volunteers, enough documentation, support, code libraries, and tools have been created to generate significant momentum behind microformats. The idea is finally becoming reality. Now, if your eyes are glazing over and any further mention of semantics, encoding, data formats, or even standards will send you straight back to YouTube, just hold on. I’m going to demonstrate that using microformats is simplicity itself. It may only be as hard as adding a class name to a single HTML element. Trust me — I’ll show you how to get the most benefit from microformats with the least amount of effort. Two of the most common forms of data being published using microformats are those relating to people and events, and I’ll cover both in this article.

Paving the Cow Paths

To borrow an analogy from the microformats.org web site by way of illustration, it can be said that microformats attempt to pave cow paths. You see cow paths every day: outside libraries, in parks, and around colleges. People always cut the corners of paved paths, make their own paths, and generally flatten the grass along the way — thereby revealing the path to the others who follow, like so many cattle. Instead of attempting to force people to follow the established paths, why not readjust the paved paths to follow the cow paths? In this way, microformats allow people to use cow paths, or rather to leverage more value and meaning out of information already published. Microformats succeed because they don’t force you to change habits: you don’t need to change what you publish, only modify your HTML slightly.Describing a Profile with Microformats

How many copies of your user profile exist on the web? Just about every site you’ve ever signed up to has a page about you, with your name, nickname, email, URL, and other basic contact information. With the use of microformats, we can make that information much more useful. Imagine being able to import your user profile from a web site into other applications without copying and pasting the text. Your profile could be aggregated across the Web to create an Internet-wide profile, saving you the trouble of having to sign up with the same data multiple times. Your friends could easily add you to their contact lists with a single click and effortlessly keep up to date when your details change. Imagine no more! hCard is a microformat designed for just this sort of role, modeled on the widely adopted vCard standard. You mightn’t know it, but your address book application has probably been importing and exporting vCards for over a decade now, while your mobile phone has been happily passing contact details around in vCard as well. There’s no sense in reinventing the wheel if something already works well — the hCard microformat benefits here, because anything that can read a vCard can easily read an hCard with only a little extra help necessary. The hCard microformat is used to mark up people, places, and organizations. The only property of hCard that is required is a name; everything else is optional. This is an important point, because one of the other microformat principles is to not change the way people are already publishing. If you’re not publishing telephone, email, or address information, then hCard doesn’t force you to begin. Let’s have a look at a very simple example, an average blogroll of a list of friends and colleagues:<li>

<a href="http://suda.co.uk">Brian Suda</a>

</li>"vcard":

<li class="vcard">

<a href="http://suda.co.uk">Brian Suda</a>

</li>Now, I’m sure some people will protest, “Hey, you’re abusing the class attribute — it’s only for CSS!” This isn’t true. According to the HTML4 spec, the class attribute is a general-purpose attribute for user-agents. Microformats are a perfectly acceptable use for the class attribute; the class attribute does not only apply to CSS. The next step in our example is to mark up the name property in the"vcard"acts like a container, saying all the data inside this<li>element is data to be considered for this vCard.

<li>:

<li class="vcard">

<a href="http://suda.co.uk" class="fn">Brian Suda</a>

</li>"fn" to the <a> element. "fn" corresponds to the vCard value FN, which stands for “formatted name” and is used as the display name in many applications.

In our example, we can add some further semantics. We have a name, but we also now have a URL. So we can add a class of "url" to the <a> element as well:

<li class="vcard">

<a href="http://suda.co.uk" class="url fn">Brian Suda</a>

</li>Describing an Event Using Microformats

Second only to information related to people and places, the most common piece of information published online regards events. People are publishing all sorts of time-related information without even realizing it. To help add more semantics to this data, the volunteers at microformats.org created the hCalendar microformat. Much like hCard, hCalendar is based on an existing widely adopted format, iCalendar. Let’s look at an example of a possible blog post:<p>

Hey everyone,

next week is my birthday party,

we should all meet up at my house for pizza.

</p><p class="vevent">

Hey everyone,

next week is my birthday party,

we should all meet up at my house for pizza.

</p>"vevent" — this addition tells a parser that everything inside this <p> element is data to be considered as related to this event. In the previous hCard example, I used an <li> element. Microformats don’t force you to use any specific HTML element, but depending on which element you do use, additional semantics can be implied.

Next, we need to add a summary that describes this event:

<p class="vevent">

Hey everyone,

next week is my

<span class="summary">birthday party</span>,

we should all meet-up at my house for pizza.

</p><span> element and adding a class of "summary", we’re saying that this piece of text is the summary for this event. We can continue marking up the location in a similar fashion; we’ll wrap the location information in a <span> element and give it a class of "location":

<p class="vevent">

Hey everyone,

next week is my

<span class="summary">birthday party</span>,

we should all meet-up at

<span class="location">my house</span>

for pizza.

</p><p class="vevent">

Hey everyone,

<abbr title="2008-05-29" class="dtstart">

next week</abbr> is my

<span class="summary">birthday party</span>,

we should all meet-up at

<span class="location">my house</span>

for pizza.

</p><abbr> element and adding a class of "dtstart", we’re saying that this data is the date-time start for this event, but the computer doesn’t know what “next week” means. Instead, because this is an <abbr> element, the parser can look to the title attribute for an answer to the meaning of "dtstart". There it finds the ISO date. If you’re wondering why I chose the <abbr> element, you can find more information about it here.

Once the information has been encoded into the text, it can easily be extracted and exported to various calendaring applications: sent locally to the computer or phone, or to remote web-hosted calendars, or shared with friends, or even distributed among mashups that are yet to exist!

So How Can I Get Started with Microformats?

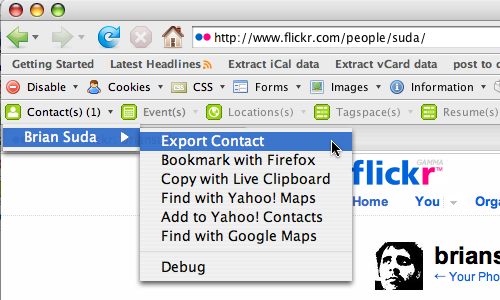

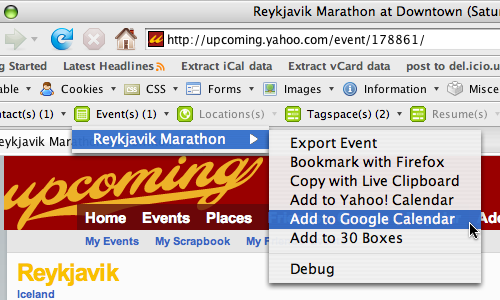

There are several tools out there that you can use to both help you create microformats and extract them usefully. The hCard creator is a web-based form that you fill out — this dynamically generates the HTML that you need to paste into your web page. Similarly, there is an hCalendar creator. There are also libraries and plugins for Dreamweaver, Textpattern, WordPress, and many, many more on the microformats hCard and hCalendar web pages. But what good does it do you to publish microformats if you can’t extract them? Well, there are plenty of tools to help you to extract and manipulate microformat data. There’s a Firefox plugin called Operator, which detects microformat content within the currently viewed web page and provides relevant options and tools. For example, if hCard content is detected, Operator will list the contact names and present an “export contact” option. This plugin is used in the example screenshots below. Operator is very handy because it not only extracts the data, but also alerts you to the presence of data on the page. Technorati hosts microformat web services for hCard and hCalendar. If you submit the URL of a web page containing hCard or hCalendar information, this web service will return the vCard or iCalendar equivalent. Technorati is also currently testing a microformats search engine. If your site’s listed in the Technorati index, they index any microformats that are found in your HTML. This data then become searchable. Eventually, you could have a tailored iCalendar subscription of only events in your city with keywords like “jazz” or “tech” or “Frisbee;” the Internet becomes your database. This is the first step toward that semantic search that has been a vision of so many, for so many years. There are libraries written for various programming languages to help you extract the microformats data from HTML for your web applications: Someone is likely working on one for your favorite language right now!Who’s Using hCard and hCalendar?

There are several organizations that have begun to encode their data using microformats: some you might have heard of, others you probably haven’t. Yahoo! is a big supporter of microformats, incorporating them into many of its properties. These include Yahoo!’s photo-sharing site Flickr, its events site Upcoming, and its tech and local sites. Flickr, as shown in Figure 1, uses microformats to mark up the user profile pages with hCard. It’s now possible to extract the user profile directly into your address book from a Flickr profile page. If you use the Operator plugin for Firefox, you’ll see that you can export the contact details to a variety of different address book clients, both locally and on the Web. Upcoming, depicted in Figure 2, uses the hCalendar microformat to mark up events. This makes using Upcoming so much easier, because even as you browse an event page you can import it directly into your calendaring application.

Upcoming, depicted in Figure 2, uses the hCalendar microformat to mark up events. This makes using Upcoming so much easier, because even as you browse an event page you can import it directly into your calendaring application.

The Yahoo! tech and local sites use the hCard microformat to mark up local companies. Now, when you search for a pizza place on Yahoo! local, it returns all results with hCards so that you can extract the telephone numbers for easy dialing.

One of the more surprising supporters of microformats has been the Cambodian Yellow Pages. This company marked up its entire phone directory with hCards — instantly creating millions of instances of semantic data on the web — just by editing one template in its content management tool.

Just to have a peek at the potential of microformats for portable social networks, let’s consider Dopplr. Currently in private beta, this an online service for frequent travellers. One day, when it’s released, you’ll be able to create a new account and import a list of your friends by submitting a URL that has content marked up with the hCard microformat. Dopplr will parse the page, extract the people, and search its database to find your friends. Dopplr also can import hCalendar data. If you plan to travel to an event, you can submit a URL with hCalendar data; Dopplr will parse it and block out those dates on your travel schedule, so your friends can keep up to date on your whereabouts.

Even recently, Microsoft has jumped on board with a brief tutorial about how to mark up the contacts in SharePoint with hCards.

The Yahoo! tech and local sites use the hCard microformat to mark up local companies. Now, when you search for a pizza place on Yahoo! local, it returns all results with hCards so that you can extract the telephone numbers for easy dialing.

One of the more surprising supporters of microformats has been the Cambodian Yellow Pages. This company marked up its entire phone directory with hCards — instantly creating millions of instances of semantic data on the web — just by editing one template in its content management tool.

Just to have a peek at the potential of microformats for portable social networks, let’s consider Dopplr. Currently in private beta, this an online service for frequent travellers. One day, when it’s released, you’ll be able to create a new account and import a list of your friends by submitting a URL that has content marked up with the hCard microformat. Dopplr will parse the page, extract the people, and search its database to find your friends. Dopplr also can import hCalendar data. If you plan to travel to an event, you can submit a URL with hCalendar data; Dopplr will parse it and block out those dates on your travel schedule, so your friends can keep up to date on your whereabouts.

Even recently, Microsoft has jumped on board with a brief tutorial about how to mark up the contacts in SharePoint with hCards.

What Does the Future Hold for Microformats?

The future looks bright for microformats! That much is made evident by the manner in which major organizations, such as Yahoo!, have perceived the potential of microformats and implemented them in a variety of ways. Likewise, browser vendors have expressed interest in adding functionality directly into the browser to detect and act on semantic markup. Imagine that the browser on your mobile phone or PDA automatically detects multiple hCards on a page. It adds a menu item to call the numbers or, if configured accordingly, it imports them directly into your address book. If there’s a postal address, the browser automatically pulls up Google Maps, and shows the location on a map. All this free movement of data doesn’t stop with contacts, however — the same applies to events and other structured data. If the browser finds hCalendar data, it can import the calendar information into the local calendar application, set reminders, and find the event location on a map. The best part about all this is that microformats are invisible to the end user. The average person doesn’t have to understand microformats or even know they are in use. Essentially, microformats facilitate this functionality for free. RSS readers are very popular these days. Wouldn’t it make sense to build similar functionality into an address book? Right now, the only way I can keep my address book up to date is by constantly copying data from friends’ emails and web sites into it. It’s a boring, repetitive, time-consuming task. With an RSS pull-style address book, on the other hand, my friends could simply publish their data online with microformats and the address book application would poll their web sites, searching for any updates. My friends and contacts wouldn’t need to spam their entire address book so as to alert everyone to the changes; they need simply update their HTML, and the next time this new address book application checks the site, it’d automatically update the local entry to reflect the changes. I’d “subscribe” to my contacts’ web page for address book updates. Many calendar applications already do this with event data, so why not with people too? These are only a few simple examples of what could be possible if publishers encoded more semantic information into their HTML. And again, in all of the above examples, the end user doesn’t need to know or care that their data uses microformats — just that it works. The microformats community is strong and vibrant. It’s very open, too, so anyone can help make it a better place by adding examples, implementations, and documentation to the Microformats Wiki. Of course, the most obvious way you can contribute is by adding microformats to your own web sites and advocating their use. With microformats, you can transform your web site content from plain text to meaningful packets of information that can be remixed and consumed in ways you may never have thought of!Frequently Asked Questions about Microformats

What are the benefits of using microformats?

Microformats provide a set of conventions for embedding structured data within HTML. They offer several benefits. Firstly, they enhance the semantic value of your web content, making it more understandable for machines. This can improve your website’s SEO performance. Secondly, they allow for more efficient data extraction and use by other applications. For example, contact details marked up with hCard microformat can be easily imported into an address book application. Lastly, they promote data interoperability, which is crucial in today’s interconnected digital world.

How do microformats differ from other semantic markup methods?

Microformats differ from other semantic markup methods like RDFa and Schema.org in their simplicity and ease of use. They are designed to reuse existing HTML/XHTML tags to convey metadata and other information, rather than introducing a whole new set of tags. This makes them more accessible to web developers and easier to implement.

Can microformats be used with any HTML element?

While microformats can be used with many HTML elements, they are not applicable to all. Microformats are typically used with structural and text-level elements like div, span, a, and img. It’s important to refer to the specific microformat specification to understand which HTML elements it can be applied to.

How do search engines use microformats?

Search engines use microformats to better understand the content of a webpage. This can enhance the display of search results, making them more useful and relevant to users. For example, a review marked up with hReview microformat can be displayed with star ratings in search results.

What are some common types of microformats?

There are several common types of microformats. hCard is used for contact information, hCalendar for events, hReview for reviews, hRecipe for recipes, and rel-tag for tags. Each of these has a specific set of properties that can be marked up.

How can I validate my microformats?

You can validate your microformats using online tools like the Rich Snippets Testing Tool by Google or the Structured Data Testing Tool. These tools can help you identify any errors in your markup and ensure it’s correctly implemented.

Are microformats still relevant with the rise of Schema.org?

Yes, microformats are still relevant. While Schema.org has gained popularity for its comprehensive vocabulary, microformats continue to be used due to their simplicity and ease of use. They can also coexist with Schema.org markup on a webpage.

Can microformats improve my website’s accessibility?

Yes, microformats can improve your website’s accessibility. By providing additional context and meaning to your content, they can make it more understandable for assistive technologies like screen readers.

How do I start with microformats?

To start with microformats, you need to understand the basic syntax and structure. Then, choose the appropriate microformat for your content and apply it to your HTML. There are plenty of resources and tutorials available online to guide you through this process.

Are there any limitations or drawbacks to using microformats?

While microformats offer many benefits, they do have some limitations. They are not as comprehensive as other semantic markup methods like Schema.org. Also, not all search engines and web applications support all types of microformats. Therefore, it’s important to consider your specific needs and context when deciding to use microformats.

Brian Suda is an informatician currently residing in Rekyavik, Iceland. He has spent a good portion of each day connected to Internet after discovering it back in the mid-01990s. Most recently, he has been focusing more on the mobile space and future predictions. How smaller devices will augment our every day life and what that means to the way we live, work and are entertained. People will have access to more information, so how do we present this in a way that they can begin to understand and make informed decisions about things they encounter in their daily life. This could include better visualizations of data, interactions, work-flows and ethnographic studies of how we relate to these digital objects. His own little patch of Internet can be found at suda.co.uk where many of his past projects and crazy ideas can be found.